We almost skipped Detroit. A lot of the news from there is discouraging. A few days into our trip, a friend texted to see if we’d reached Michigan yet. “Don’t miss Detroit!” she exhorted. (There are a bunch of Michiganders in Lubbock, and they have an enthusiasm for their home state akin to Texans.) I’m so glad we visited. Every person we met, even the server at a tiny restaurant in a distressed neighborhood where we dined, expressed enthusiastically that Detroit is a city focused on comeback. I loved the cheerful energy of all the folks we encountered.

First, we visited the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn. What I thought would be a two-hour visit stretched to four, and we had to run to catch the bus to the Rouge Factory, or we’d have stayed longer. The museum is a shining monument to planes, trains, automobiles, and all the big machines that fueled the industrial revolution. I’m not very mechanically minded, and I often wonder at the things Brandon and his brother, Jason, can figure out by tinkering. They get it from their granddad by way of their mama. She can tinker, too.

Steam locomotive, in use until the 1950s.

Model T, in parts

I graduated from highschool in Fort Valley, GA where the first school bus was constructed by Albert L. Luce, a Ford dealer. In Peach County if your parents didn’t farm, there’s a good chance they worked at Bluebird.

Rosa Park’s bus

The kids spent a long time building Lego cars and making paper airplanes to test.

We couldn’t take any pictures at the Rouge Factory, where thousands of workers were assembling Ford F-150s, but the sight left indelible images on our brains. We’d already tried out a mini-assembly line at the museum. (We were pretty good; there was only one recall, and we were faster than average in assembly time.) But to see something of that scale in action! Wow. Now our conversation about labor, which started back in OK with Woody Guthrie, was fully fleshed as we learned about Ford’s $5-work-week and his evolving response to unions.

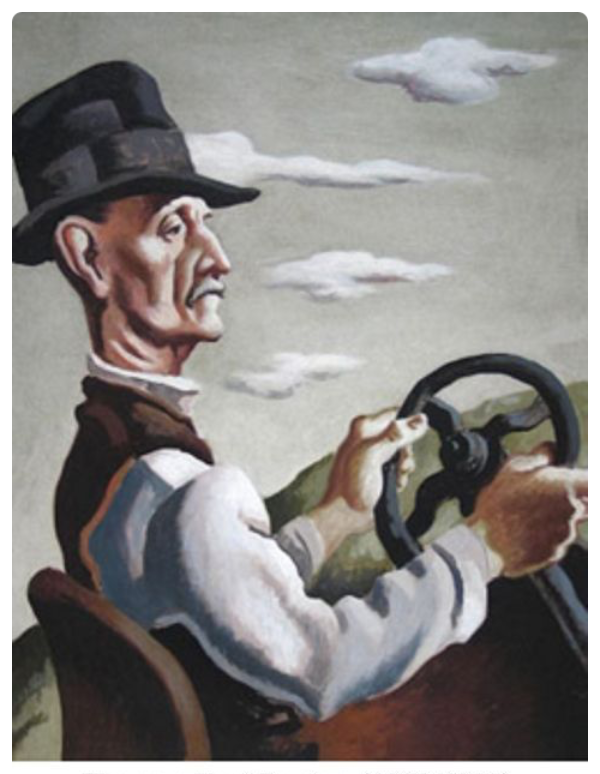

I can show you Diego Rivera’s pictures of the Rouge from the 1930s. They stretch up and down the grand entry of the Detroit Institute of Arts. Most of Rivera’s work is in Mexico. It’s on the exterior of buildings, so the public has easy access to it. Given that Nelson D. Rockefeller fired Rivera from a similar job in New York and famously destroyed the work because Rivera included a portrait of Lenin in the mural, it’s surprising this project didn’t meet more resistance. Depicted is a cautionary tale of the blessings and curses of industrialization, and it makes some pointed statements about labor and management. The morphed portrait of Ford and Edison is positioned on the same level as a laborer, and right behind management is a piece of machinery shaped like a huge ear. I could go on and on about these murals! The docent for the Rivera Court chatted away for at least thirty minutes, pointing out little details that emerge from the murals if you look long enough. Riveria painted frescos, like he’d seen in public buildings in Italy, and he worried the workers who prepared the plaster by breezing in at the last possible moment. He completed the murals in just eleven months.

I found a painting of Tobias and the Archangel!

We couldn’t leave town without a visit to the Motown Museum. The entertaining tour guides, alone, are worth the ticket! We visited two of the eight homes on West Grand Boulevard that originally housed Berry Gordy’s 24-hr-a-day, 7-day-a-week hit factory. Gordy’s parents moved to Detroit from Sandersville, GA during the Great Migration, and they immediately excelled in multiple business ventures. A defining characteristic of the whole family was their commitment to excellent, energetic work. We saw the desk where Diana Ross worked as a secretary and the candy machine where someone always left a dime on top for Stevie Wonder, who loved the Baby Ruth candy bars that were always kept in the fourth slot from the right. At the end of our tour we got to sing “My Girl” in Studio A. In the old days, artists and producers met to evaluate new songs. To test for “hit” quality, they were asked if they had one dollar left, would they buy that song or a sandwich. We thought we sounded pretty good, but maybe not better than a sandwich on an empty belly.